[ad_1]

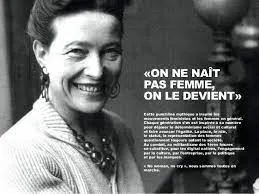

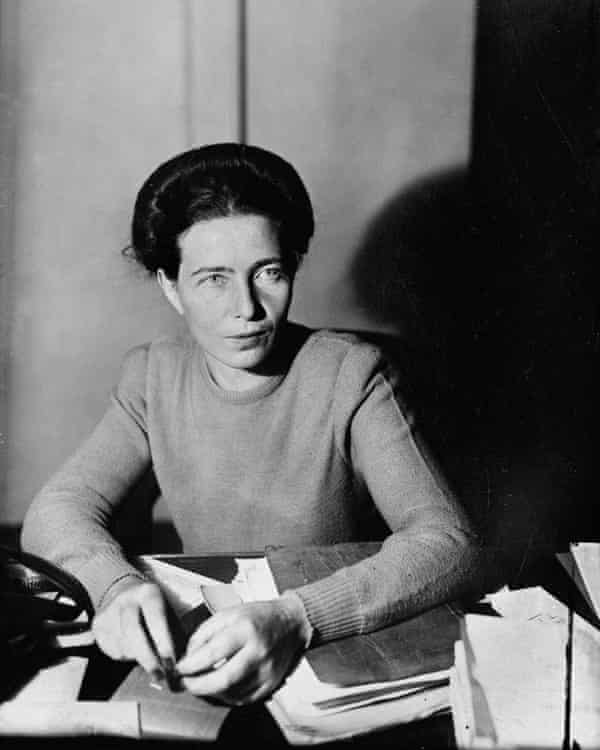

Written 75 years ago but deemed ‘too intimate’ to publish in her lifetime, this exclusive extract from a lost novel by the author of The Second Sex, translated by Lauren Elkin, is based on the ‘passionate and tragic’ friendship she had as a girl with Elisabeth ‘Zaza’ Lacoin

When I was nine years old I was a good little girl, though this hadn’t always been the case. As a small child the adults’ tyranny caused me to throw such tantrums that one of my aunts declared, quite seriously: “Sylvie is possessed by a demon.” War and religion tamed me. Right away I demonstrated perfect patriotism by stomping all over my doll because she was made in Germany, though I didn’t really care for her to begin with. I was taught that God would only protect France if I were obedient and pious: there was no escaping it. The other girls and I would walk through the basilica of Sacré-Cœur, waving banners and singing. I began to pray frequently, and I developed a real taste for it. Abbé Dominique, the chaplain at the Collège Adelaïde where we went to school, encouraged my ardour. Dressed all in tulle, with a bonnet made of Irish lace, I made my First Communion, and from that day forward, I set a perfect example for my little sisters. Heaven heard my prayers, and my father was appointed to a desk job at the Ministry of War because of his heart trouble.

That morning I was especially excited because it was the first day of school. I couldn’t wait to get back to the classroom, solemn as a Mass; the silence in the hallways; the softened smiles of the teachers, in their long skirts and their high-necked blouses, who were often dressed as nurses since the school had been partially turned into a hospital. Under their white veils with red stains, they resembled saints, and I was overcome when they pressed me to their bosoms. I wolfed down the soup and grey bread which had replaced the hot chocolate and brioches from the prewar days, and impatiently waited for my mother to finish dressing my sisters. All three of us wore sky-blue coats, made of real officer’s serge and cut exactly like military greatcoats. ‘Look! there’s even a little martingale at the back,’ my mother would show her friends, who were admiring, or taken aback. My mother held my sisters’ hands as we left the building. We walked with sadness past Café La Rotonde, which had just opened noisily beneath our window, and which was, Papa said, a hangout for defeatists. I found the word intriguing. ‘Defeatists are people who believe that France will lose the war,’ Papa explained. ‘They should all be shot.’ I didn’t understand. We don’t believe what we believe on purpose; can you really be punished for the things you think? The spies who handed out poisoned sweets to children, or pricked Frenchwomen with needles full of venom in the metro – obviously they deserved to die, but the defeatists baffled me. I didn’t bother asking Maman; she always said the same thing as Papa.

My little sisters walked slowly; the wrought-iron grill of the Luxembourg Gardens seemed to go on for ever. Finally I arrived at the school gate and climbed the front stairs, joyfully trundling my satchel overflowing with new books. I recognised the faint odour of illness, mingled with the smell of wax on the freshly polished floors. The teachers kissed me. In the cloakroom I was reunited with my schoolmates from last year; I didn’t have any particular attachments among them, but I liked the noise we all made together. I dawdled in the main hall, looking at the display cases full of old dead things that came here to die a second time – the feathers fell from the stuffed birds, the dried plants turned to dust, the shells lost their shine. When the bell rang, I entered the classroom they called Sainte-Marguerite. All the rooms looked the same; the students sat around an oval table covered in black moleskin, which would be presided over by our teacher; our mothers sat behind us and kept watch while knitting balaclavas. I went over to my stool and saw the one next to it was occupied by a hollow-cheeked little girl with brown hair, whom I didn’t recognise. She looked very young; her serious, shining eyes focused on me with intensity.

‘I’m Sylvie Lepage,’ I said. ‘What’s your name?’

‘Andrée Gallard. I’m nine. If I look younger it’s because I got burned alive and didn’t grow much after that. I had to stop studying for a year but Maman wants me to catch up on what I missed. Can you lend me your notebooks from last year?’

‘Yes,’ I said. Andrée’s confidence and rapid, precise speech unnerved me. She looked me over warily.

‘That girl said you’re the best student in the class,’ she said, tilting her head a little at Lisette. ‘Is that true?’

‘I often come in first,’ I said, modest. I stared at Andrée, with her dark hair falling straight down around her face, and an ink spot on her chin. It’s not every day that you meet a little girl who’s been burned alive.

This is an extract from Simone de Beauvoir’s novel The Inseparables, translated by Lauren Elkin, which is published on 2 September by Vintage Classics (£12.99). To order a copy go to guardianbookshop.com or call 0330 333 6846. Free UK p&p over £15, online orders only. Phone orders min p&p of £1.99

[ad_2]

Source link