By Kelly Grovier | 19th August 2021An exhibition about Iran traces how some of the world’s earliest scripts developed. They were as much about images as text, writes Kelly Grovier.

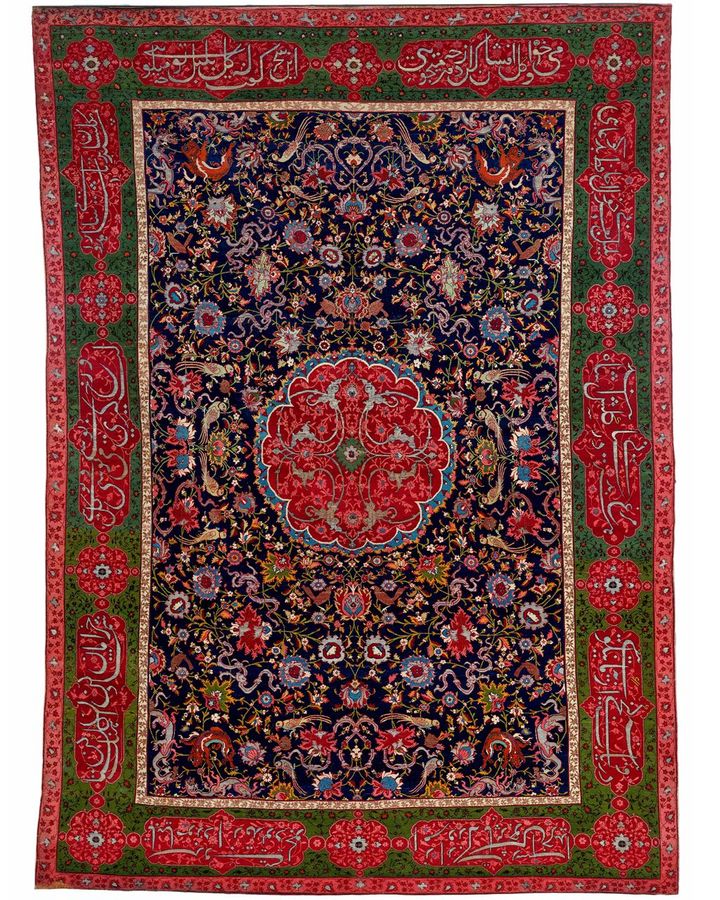

“What more do you want from your time here?” The existential question, posed by the 14th-Century Persian poet Hafiz, is woven into a dazzling 16th-Century carpet that is among the treasures showcased in the Victoria & Albert Museum’s vast exhibition Epic Iran, 5000 Years of Culture, and in the lavishly produced catalogue that accompanies the show. Thornily thought-provoking in itself, the probing fragment of verse belongs to a sequence of five couplets from a ghazal (a medieval Arabic verse-form typically devoted to the subject of love) that is stitched into the border of the silk, wool, and metallic-thread carpet, providing a calligraphic frame for the pattern of intricately interlocking flowers and birds that sprawls across the textile.

At the very centre of the carpet, a rosette bursting with stylised stamens and flaming petals seems at once the lips that whisper the enigmatic lines borrowed from Hafiz and a product of their intoxicating vision: Call for wine. Scatter blossoms. What more/do you want from your time here?/At dawn, the rose spoke these words,/”Nightingale, what are you talking about?”

The lyric weaves a fragrant hallucination, the logic of whose stream-of-consciousness threads are often more evocative and equivocal than clear in a ghazal. The universe is a befuddling dream of “scatter[ed]” images, deceptive scents, and ambiguous utterances. The question is, how do you and I figure in the illusive tapestry of touch and taste, sight and sound? Like the indeterminate relationship between Hafiz’s poem and the design it encircles on the hypnotising carpet, we too are juxtaposed mysteriously against the warp and weft of a world we are at once a part of, and are merely passing through like the eye of an embroiderer’s needle.

The connection between words and images points to something fundamental about the nature of how we comprehend who we are

The connection, in other words, between words and images – between what is said and what is seen – is poignant and points to something fundamental about the nature of how we comprehend who we are and what more we want from our time here. “The presence of the poetry,” Tim Stanley, co-curator of Epic Iran tells BBC Culture, “makes the carpet not just a thing you sit on and not just a pretty pattern. It’s got this poem on it which shows that it belongs to a sophisticated world.”

If not a “direct relationship”, how can we characterise the alluring symbiosis between what the carpet seems to say and what it purports to show? Clearly, the imagery of the carpet does not “illustrate” the poem. Nor is the poem in any sense a “caption” on the imagery. Instead, the two cohere holistically, and form something greater than the sum of its parts. Such a merging of art for the eye and ear, or synphrasis (meaning “to speak together”), is the spirit that enlivens many of the masterpieces of the V&A exhibition. For many Iranians, that intriguing intertwinement of word and image is felt in the blood, and felt along the heart. It is part of who they are. “The way the poetry relates to art,” Stanley says, “goes beyond the idea of a narrative supplying a story which you depict in an illustration.”

Though verbal and visual arts are often conceived separately in the West, their intrinsic entanglement in cultural consciousness in Persia can be traced back to the very inception of writing in the region. Among the first objects that visitors to Epic Iran will encounter is a small clay tablet discovered in Susa, an ancient city in the lower Zagros Mountains, in 1905. Archaeologists believe the tablet, written in Proto-Elamite script, was created as early as the 4th millennium BC, making it one of the very oldest known written documents ever excavated. Its curious syntax of inscribed crosses, crescents, and lunar discs, which are thought to tabulate the yield of a handful of fields, suggests just how intricately intertwined the patterns of visual and verbal communication were from the start.

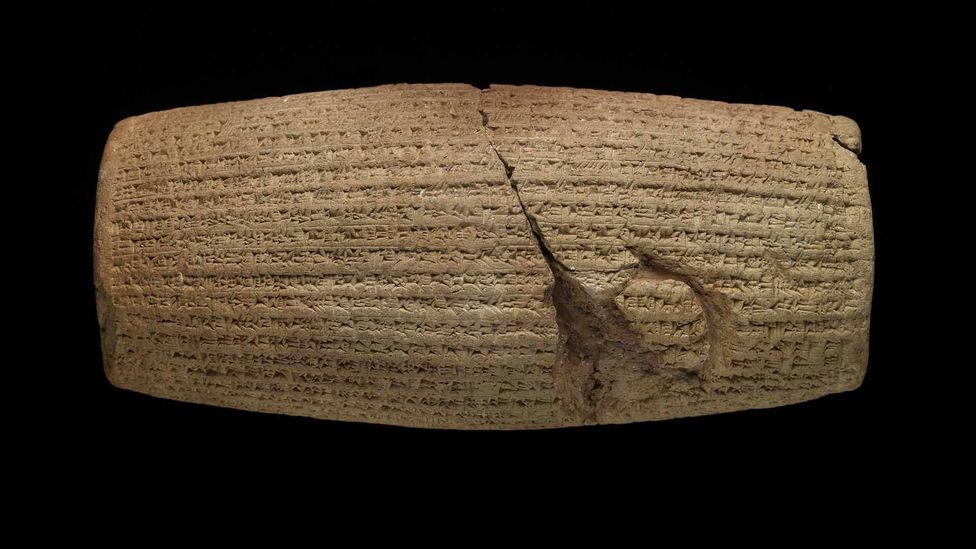

Fast forward 25 centuries, and that same instinct to bobbin together with a single thread an object to behold and a text to read is a key contour of one of the most cherished items in the exhibition. The so-called Cyrus Cylinder, created between 539 and 538 BC, is a barrel-shaped ceramic that chronicles the conquest of Babylon by Cyrus the Great. Remarkably, it also records Cyrus’s seemingly compassionate resolve to allow people deported by the previous king of Babylon to return to the city and to bring with them statues that had been removed from their vanquished temples.

The tubular tablet, whose text conceptually rewinds as you spin it, suggests a ceaselessness to Cyrus’s command. Its physical shape and the shape of its message are coterminous and without end. “It’s sort of iconic,” Stanley says, (describing the Cyrus Cylinder as “the standout object in terms of an art object that’s loved in Iran”) “and very close to people’s identity as Iranians. It gives an idea of the attitude of the founder of the Persian Empire about how he’s going to deal with all these non-Iranian people… It’s a very unexpected shape. Considering the size of most cuneiform documents that come down to us, it’s quite large and impressive.”

That same sensitivity to the synergism of physical shape and linguistic meaning invigorates the trove of treasures showcased in the section of Epic Iran devoted to “Literary Excellence”. Though seemingly far removed from the concerns of an antique fragment boasting of a bygone Babylonian conquest, an exquisite copper torch stand from around 1600 – on which are engraved a pair of charming couplets by a predecessor of Hafiz, the 13th-Century Persian poet Sa’di – reveals how that early inclination to merge shape and syllable continued to flicker undiminished for centuries. Around the top of the 28cm-tall torch stand, an extract from a poem by Sa’di imagining an intimate chat between a moth and a candle animates the static object with unexpected poignancy and wit: I remember that one night when I lay awake/I overheard a moth in conversation with the candle,/”I’m love-struck,” he said. “So it’s right and proper I should burn./But you, why these tears? Why burn yourself up?”

The artist who fashioned the torch stand was aware that observers of his handiwork would know by heart the full exchange between the two unlikely interlocutors, and would be able to supply from memory what isn’t explicitly inscribed. The candle’s soulful reply to the moth in Sa’di’s poem, that it too has lost its love (its “honey” – a sweet play on the beeswax that melts into waxen tears dripping down the candle’s side) is all the more moving for its absence. The convergence of the torch stand (as a pedestal on which the candle, a symbol of life’s fleetingness) with Sa’di’s lilting lyric, elevates the object from mere utility into something meditative and profound. At the same time, the combination of the two preserves the poet’s words and ensures that it doesn’t dissolve into pointless whimsy.

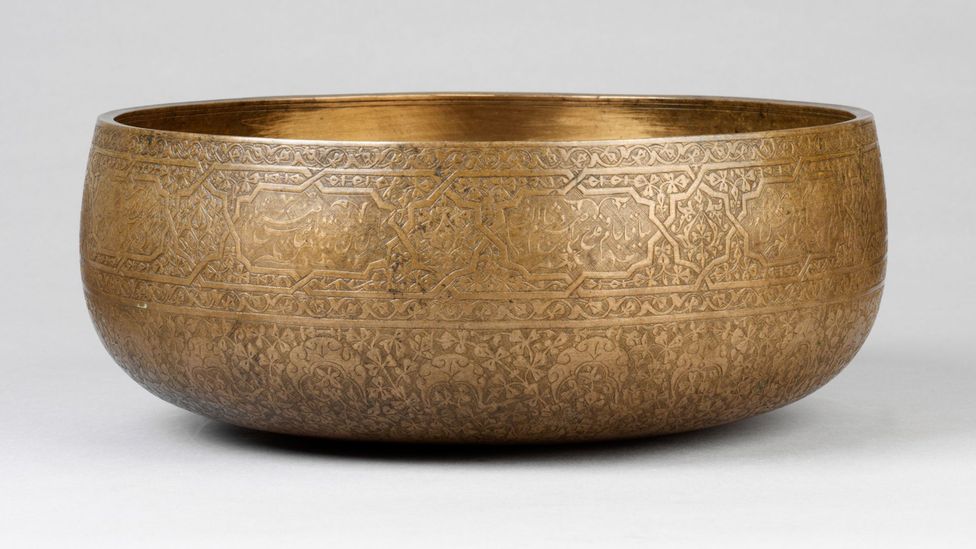

This finely finessed fusion of form, phrase, and function also energises a beautiful bell-metal wine bowl from the early 16th Century. The vessel’s essential union of shape and script is underlined by the unusual appearance on its surface of signatures by both the maker of the vessel, Ustad Muhamud Ali, and the gifted calligrapher, Sultan Muhammad, who interlaces a ghazal by a contemporary poet, Hilali, into a hypnotic design that encircles the bowl.

Sultan Muhammad is aware of the perfect compatability of Hilali’s lines with the reflective brilliance of the spun bell-metal interior of the object, whose radiant sheen lures one’s gaze inside the bowl like a flame beckons a moth. “When the beloved observes his rose-coloured cheek in the wine-cup,” the engraved poem begins, “the reflection of his face makes it a fountain of the Sun”. Once again, the merging of the visual and the verbal creates a transcendence that is otherwise unachievable.

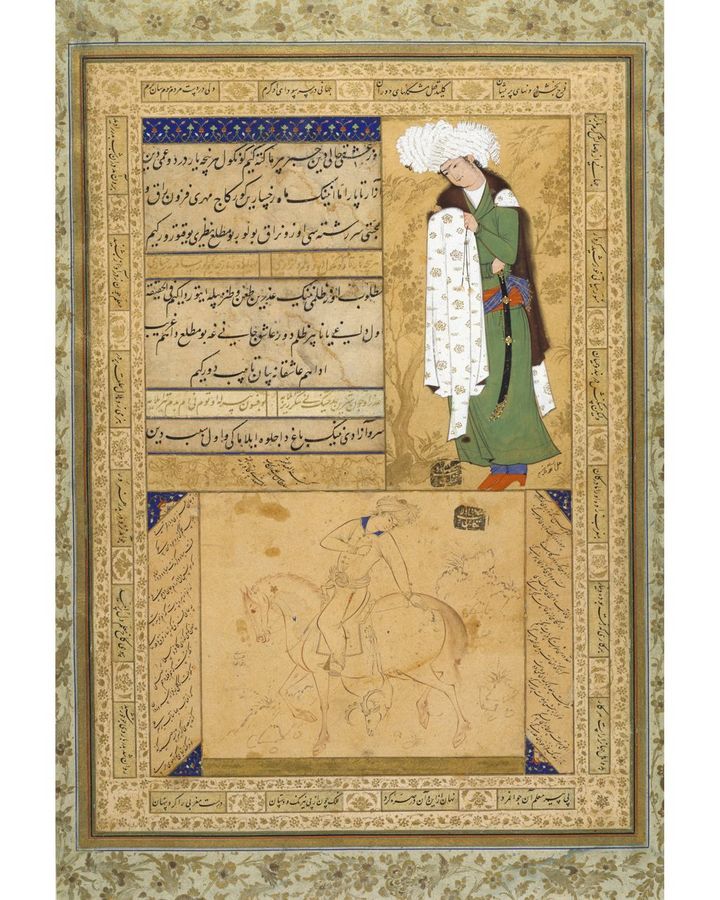

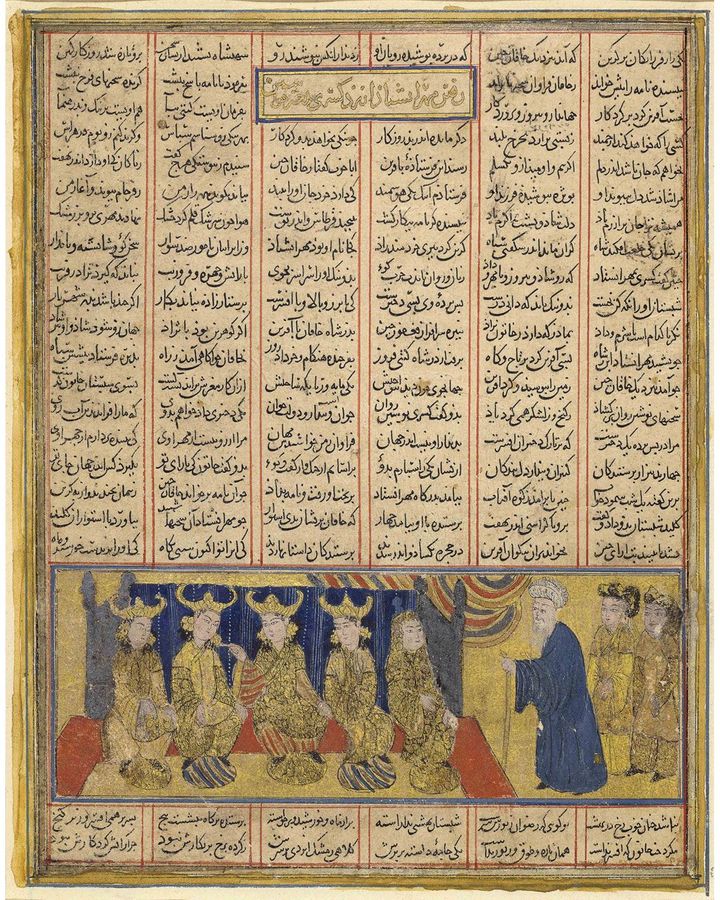

To trace the evolution of this fascinating synergism between language, image, and form in Iranian art, design, and literature is to mark the development of calligraphy, which embodies the blurring of lines between linguistic legibility and pure pattern. The range of manuscripts featured in Epic Iran allows visitors and readers to observe the gradual transformation of calligraphic style from the relatively simple naskh (or “book hand”) script – seen surrounding a watercolour of a court poet reading his verses to the sultan in a 14th-Century folio – to the more elaborate and free-flowing nasta’liq script, in which a lavish 15th-Century collection of Sa’di’s poems is written.

In the past, Western curators, failing fully to appreciate the interdependence of aesthetic parts, all too often severed the beauty and achievement of the calligraphic text from the intensity and wonder of the images it surrounded. Correcting that misconception, which was a notable shortcoming of the last major exhibition in the UK devoted to Iran (almost a century ago, in 1931 at the Royal Academy of Arts), is among the aims of the current exhibition – and of the eloquent catalogue (written by the co-curators Stanley, John Curtis and Ina Sarikhani Sandmann) that accompanies it.

The misapprehension about this fundamental aspect of the Iranian creative imagination is symptomatic of a broader failure fully to appreciate the extraordinary and formative contributions that Iran has made these past five millennia. “The idea of the show,” Stanley explains, “is to foreground the fact that Iran is one of the great civilisations. It doesn’t really get a lot of recognition for that. We wanted to illustrate how incredibly beautiful and interesting the country of Iran is.” To that end, Epic Iran aims to wipe the slate clean, and reset our understanding by retelling the story of civilisation with Iran restored to its position among the crucial cradles of human culture.

“In the 30s,” says Stanley, “people were thinking about the birth of civilisation. They had heard about Ancient Egypt and they knew about the Fertile Crescent, especially Iraq and Mesopotamia. But they didn’t know anything about Iran. And so Iran wasn’t at the table when the birth of civilisation was being talked about. It’s only when Iran’s own archaeologists started to work on sites all over the country in the 60s, nearly, that it was realised that civilisation started in Iran much earlier than people had realised, and that it was much more important and interesting than people had realised.” Remembering where we come from may help us know where we are and where we’re headed, how our syllables fit into the tapestry, and what more we want from our time here.

Epic Iran is at the V&A in London until 12 September 2021.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.