/

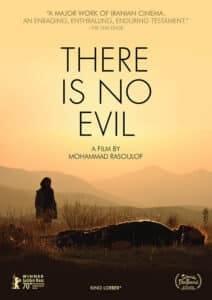

The original Persian title of Mohammad Rasoulof’s There Is No Evil is Sheytân vojūd nadârad, which means “Satan doesn’t exist”. That’s the better title, for its implication is that people’s choices create the world’s evil. Under any title, this happens to be a great film, and something better: a brave one.

Rasoulof’s film, made of four thematically related “moral tales” running two and a half hours, won the Golden Bear at the 2020 Berlin Film Festival. Rasoulof couldn’t attend. Like his compatriot Jafar Panâhi, with whom he’s collaborated, Rasoulof remains under house arrest, banned from making films, and lives under a prison sentence that, as far as I can determine, has yet to be carried out but hangs over the men’s heads.

While “under arrest”, they carry on with their lives, covertly making films on digital video and sending them to festivals. Rasoulof even served as a judge in the 2021 Berlin Festival, from his home. Panâhi and Rasoulof have made 17 features between them, and the lion’s share of their films are masterpieces. If Nobel Prizes for literature were handed out to screenwriter-directors, these two would deserve a shared award. Are you listening, Stockholm?

This surreal state of affairs, this living under arrest and sentence, may be due to a combination of COVID and Kafka, but the beautiful irony is that it hardly matters, for the Iranian government does its best to support the ruling metaphor in Rasoulof’s body of work: his country as a prison.

His debut feature, The Twilight (Gagooman, 2002), concerns the relations between an inmate and the thoughtful warden who wants him to settle down and find a wife. I’ve seen this film but not his next, Iron Island (Jazire-ye Ahani, 2005), described as a parable about a benevolent dictator who takes care of poor families crowded into an offshore tanker.

Another feature is Manuscripts Don’t Burn (Dast-Neveshtehaa Nemisoozand, 2013), which I reviewed for PopMatters. I observed that some characters are tools of the state, “who plod about the business of torture and murder while fretting about their own problems. For at least one of them, the mental and spiritual fallout of his job is reinforced by the awareness that he’s just as disposable as his victims.”

I also described something of the low-key, mundane yet intense and restless suspense generated through careful observation. “As with many Iranian films, it takes an unblinking, unhurried, observational pace as the camera allows its characters to live in the moment. They walk, they stand, they think, they drive, they look around, they slip a bag over someone’s head, they smoke a cigarette.”

Why am I writing about his other films here instead of this new one? Partly to show they’re all of a piece on the theme of life as prison and prison as life, and partly because I feel I can’t really discuss the themes of There Is No Evil more explicitly. Even though its primary subject is discussed in every review and description, it came upon me as a brutal shock, since I don’t read about films prior to watching them, and I’d rather not give it away here.

Shot secretly in widescreen splendor, the first story focuses on a middle-class, middle-aged, middle-flabbed functionary named Heshmat (Ehsan Mirhosseini) driving home. He picks up his wife, Razieh (Shaghayegh Shourian). They argue about this and that, like a longtime married couple, as they go about their errands.

Much of this segment shows the driver, with or without his wife, driving his car. Sometimes the camera looks out the windshield. These “driving” motifs are common in Iranian cinema, especially in films of Abbas Kiarostami, who knows how much of our lives we spend in our vehicles. I find driving to be especially cinematic, and the glassed images and reflections provide moments of visual poetry here.

As I’ve hinted, something will happen that defines the theme examined in the next three stories, and that theme involves personal choice when confronted with participation in evil. Without recurring characters, each story expands on the resonances of the previous story.

There’s some discussion about resistance, or the power of saying no, vs. accepting your lot, following orders, obeying the law. That’s why four stories are presented, each in a different locale: city streets, prison walls, lush forest, arid hills.

Two stories explore the consequences of failure to resist, while two explore the consequences of resistance. This thoroughly worked-out scheme manages to grip and surprise the viewer even as the stories unfold in leisurely scenes, sometimes in “real-time”. The second story takes place almost entirely in handheld real-time, and its suspense is almost unbearable.

In addition to the artfully constructed central mysteries of each story, as gradually revealed, the tales also have mysterious minor details and symbols to intrigue and distract us. For example, the opening shot involves Heshmat and another man dragging something across the floor of the parking garage to the trunk of his car. We’ve seen enough films with this kind of thing to put us on the alert, justifiably or not, as though this is the Iranian Goodfellas (Martin Scorsese, 1990).

The second story refers to the contents of a mysterious note. The third story gives us a shot of a man’s feet in a way that can’t help but remind us of an earlier image, and also the man bathing in a river that may remind us of an earlier shower scene. We’re given a hauntingly gratuitous yet relevant image of a uniform draped in a tree like a scarecrow, a stick man. The fourth tale keeps lingering on a rifle, in haunting defiance of Chekhov’s famous dictum about a loaded gun.

Also in the cast: Kaveh Ahangar, Alireza Zareparast, Salar Khamseh, Kaveh Ebrahim, Pouya Mehri, Darya Moghbeli, Mahtab Servati, Mohammad Valizadegan, Mohammad Seddighimehr, Jila Shahi, and Baran Rasoulof. As a precaution, the cast and crew of Manuscripts Don’t Burn didn’t receive credit, but this film lists its participants in all their quiet audacity and tenacity. The disc has no extras.

I haven’t seen a better new release thus far this year.